AK: Who are you? Where did you grow up and where are you now based?

MW: My

name is Michael Woods, but for creative purposes I go by M. Woods. I

was born in New York City to a single mom. My mother was born in

Costa Rica; my grandmother being originally from Puerto Limon, Costa

Rica, and my grandfather and his family are from Ambato, Ecuador. I

went to most of grade school and high school in Evanston, IL (where

Northwestern University is located), before returning back to New

York City to attend NYU’s Tisch School of the Arts, majoring in

film production. I’m now based in Los Angeles, where I work, teach,

exhibit, and make my creative work with whatever time I have left.

AK: Could you give us a brief history of your involvement with creating

work involving still or moving images?

MW: As

a kid, I was bullied incessantly from the age of 6, so I used movies

as a sort of retreat/escape. My step-father (who I regard as my

father) introduced me to writers like Edgar Allan Poe and Franz Kafka

at an early age, while also introducing me to 2001: A Space Odyssey

at the age of 9. The experience of the Stargate sequence initially

sparked my interest in making films – to recreate the sort of

transcendental experience I did not have the words to express at the

time. I continued a rabid addiction to movies, until I watched

Mulholland Drive at the age of 13. That was the experience that sparked

my pessimism towards motion picture and allowed me to become

conscious of the way in which my personality was an amalgamation of

motion picture simulation. That I did not feel like an authentic

self. The movie communicated to me on a ground I had never

experienced before and may never experience again; but if Lynch pulls

the rug out of the movie, he is similarly attempting to pull the

false reality out from underneath the spectator, so as to direct

their consciousness towards the spectator/spectacle relationship,

while simultaneously drawing the viewer towards a practice of

self-reflection that helps to spark consciousness.

Once I was

convinced that this consciousness could be spread through media, I

embarked on a project called The Numb Spiral. The origins of the Numb

Spiral also reflected my state of drug addiction and self-destructive

behaviour. At the age of 15/16, I began to experience bullying that

was so constant and aggressive that I began to drink, smoke

marijuana, abuse prescription pills like Vicodin and Adderall, but

most pathetically, I began to consume cough syrup on an almost daily

basis. The cough syrup in question had only one active ingredient –

Dextromethorphan – which is a disassociative anaesthetic. A

disassociative anaesthetic creates a feeling of total numbness, which

causes the illusion of “out-of-body” experience when taken at

higher doses. Conscious of my own descent into a place divorced from

physical reality, I tried to channel my addiction into a creative

obsession, and as I became clean, I created a “production company”

– essentially a label for all of my films – which would become

Disassociative Productions. The first and only project that

Disassociative Productions has been working on is an art cycle known

as The Numb Spiral. The "Numb Spiral” is a term I use to

describe the parasitic nothingness at the heart of American culture.

This is a nothingness that can be broadcast, ingested, used as the

basis for societal norms and conventions; it is at the heart of

currency, politics, corporate culture, and racial hierarchies. This

corrosive nothingness operates similarly to The Precession of the

Simulacra as illustrated by Baudrillard, the Spectacle as

illustrated by Guy Debord, and is further elucidated in Being and

Nothingness by Sartre. I began using the work of Freud and Jung to

better come to grips with the way in which this nothingness has

evolved to augment the original psychical models they introduced. In

short, the "Numb Spiral” is the moment in which consciousness

falls into Sartrean “Bad Faith”. In this “Bad Faith” model,

nothingness or illusion is taken to be as “real” as the facticity

of physical reality. (Facticity being a term that Sartre coins to

define the ground of physical reality that exists despite and as the

fountain of human existence.) The “Numb Spiral” is the moment in

which human consciousness completely loses that ground, and the super

ego projects an illusion of reality – the individual succumbing to

the heart of hyperreality. In my own experience of this “Numb

Spiral”, a sort of void fills reality that enables consciousness to

posit nothingness over everything, and in doing so the false lure of

completely malleable existence entices the conscious mind.

What I

found, however, is that experiences like Mulholland Drive are

able to counteract the hyperreal; media, most importantly motion

picture and immersive media, posit themselves as real when they are

instead falsehoods. They are false representations of reality meant

to force the spectator into a real reaction towards the illusion. In

the work of Lynch, for instance, Lynch uses this construct to build a

formidable illusion, but every one of them begins to fall prey to its

own falsehood. In this way, Lynch is creating consciousness with

motion picture. Just as human beings posit nothingness in order to

allocate themselves as being here in everything, Lynch uses the false

reality of motion picture to point back at its own negative

structure. In doing so, in telling the whole truth through an

artificial construct, Lynch is terrorizing the media. It was with

this in mind that I began using all art to accomplish the same goal;

I am a media terrorist, aimed at exposing the nihilism at the heart

of the artifice, while expressing through it in order to transcend

and reverse the effects of hyperreality. It is a Quixotic quest, and

on my work desk I have small figurines of Don Quixote and Sancho

Panza clearly visible to remind me of my naivete along the way. But

using both digital and analog means allows me to explore the

different dimensions of media; in adopting a hybrid media practice,

I’m able to call upon the nostalgias and memories associated with

different media types/film gauges. While the main thrust of my work

remains the same throughout this 13 year + period of the Numb Spiral,

I experiment with different ways of recording illusions and then

intervening through direct and digital manipulation. At first my work

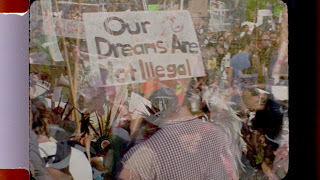

was not overtly political, but through the past decade I have grown

more aware, especially as a White-passing Latino, of the need to

include racial politics in my work, especially as we continue to

trudge through Trump’s ham-handed hyperreality. Especially Aldo

Tambellini and Spike Lee have driven me to make my politics more

visible. If anything, the politics have started to catch up to my

work, and Trump is now a very fitting backdrop to the sort of

surrealism that pervades my work.

AK: What were the major influences in the arts and in life which encouraged you to become involved with this field?

AK: What were the major influences in the arts and in life which encouraged you to become involved with this field?

MW: The

folks above, definitely, but also all of the real avant-gardes: Dada,

Surrealism, Lettrists/Situationists Intl, Hip-Hop. The RZA and J

Dilla, as samplers, are extremely necessary to my work. Wu-Tang Clan

in general has a similar model in hip-hop, theoretically, to what I’m

exploring in motion picture, and I have adopted some elements of

their business plan as well. De Beauvoir, Malcolm X, William S.

Burroughs, Jodorowsky, Deren, Menken, Anger, Bergman, Akerman,

Breillat, Bunuel, Godard, Rivette, etc… numerous obviously, but all

approach their art with a similar set of ethos and politics. My

direct mentors have been Jason Halprin, Fred Worden, Bruce McClure,

Aldo Tambellini, Pipilotti Rist, Lynne Sachs, Marco Williams, and

Darrell Wilson, all of whom have shown me different ways of looking

at motion picture and performance, documentary vs. narrative,

experimental, video art… etc…

AK: What does the word “experimental” mean to you?

MW: Experimental

to me simply signifies a new way of expressing that has not been

forged before, or at least there is an implication that the

experimenter is taking an uncharted route down a previously explored

path. To work in experimental film does not mean to acknowledge and

hold dear those previously heralded or currently thought of as the

most important. I think the term “experimental” implies

avant-garde, but not in the current configuration of academic

“experimental film.” Academia defined “experimental film” and

the related film festivals often choose work that does not

experiment, but rather re-treads down the same path for the purpose

of fitting in with trends defined by those in power. My work is often

not shown at “experimental” film festivals as a result of it not

fitting the programming – especially as the scene in the United

States celebrates work that is sometimes outright boring. In general,

I do not like Structuralist work, though there are a few artists like

Ernie Gehr, who interest me despite the goals being radically

different from my own. I think the Structuralist movements view

“experimental” in the way a scientist would as opposed to the

brazen artists I am most interested in. When it comes to art, I do

not have time for subtleties anymore, especially as we live in a

world that is so obscene. I find them to be inauthentic and

representative of the bourgeois state of “experimental film.”

AK: At Avant Kinema we have a particular interest in low budget, DIY or

LoFi forms of creativity. What are your thoughts on films, music,

zines or other artworks created in this way? Is this a way that you

personally like working?

MW: I

do not treat working low-budget or DIY as a badge of honor, but

rather as a necessity. I am not capable of buying or receiving the

same resources as many other “experimental filmmakers” so I’ve

had to draw out my process over the course of a decade. Sometimes

that means not having the money or the wherewithal to process film to

months or years later. Sometimes that means not having the resources

to complete a scene or a movie until years later. I think the plight

of the underground filmmakers, the working filmmakers, those who have

to make work in their free time – because we do not have the

opportunities of our bourgeoisie counterparts – is not something to

celebrate necessarily. It is just the way we have to do things. If

I’m given a budget, I will immediately take the money. I want as

much money as possible. The ideas I have are feature films, ones that

I want shot on 35 & 16mm. I don’t buy the premise that more

money means less creativity. I think we sometimes have a tendency to

use low budget or DIY as a badge of honor. In reality, at least for

me, it is a constant struggle, and if I had the resources that I see

a lot of our bourgeoisie counterparts have, I would be more prolific

and more easily able to put out the work that has otherwise taken me

13 years to bring to fruition. However, the thing that binds us –

those of us bound to create despite these limitations – is an

inherent ingenuity, and an obsession that transcends our financial

situation. Even I, however, recognize that despite living paycheck to

paycheck (if that), I have more resources and more opportunity than

many who remain voiceless because they do not have the wherewithal to

contribute to our art. In that sense, I am a champion for underground

and emerging art, especially from those who share the struggle to

make their work.

AK: What was your earliest experience of using analogue film, video or

photographic equipment?

MW: My

first experience using analog film was in a Fisher-Price toy 35mm

camera when I was a child, but I began to use it seriously at the age

of 17 when I was an intern at Chicago Filmmakers – which hosts the

Onion City Experimental Film Festival. I learned how to use Super-8

from playing around with an old Elmo Super-8 and that footage served

as the basis for my upcoming feature film, Disneyworld. I was taught

to use 16mm by Jason Halprin, initially, and then at NYU I made my

first 16mm shorts in Joanne Savio’s Sight and Sound Film Class

under the tutelage of Geoffrey Erb, a cinematographer who had worked

on Law & Order. He’s now passed away, but a lot of my

cinematographic tricks come from Geoff. I started on an Arri-S while

I was in school, but soon began working with the school’s Arri-SR,

and I managed to purchase my own Beaulieu R16, and later a Bolex when

the R16 broke. I still shoot 16mm on a nearly daily basis – having

hoarded film when I was eligible for a student discount. I also shoot

super-8 with a Beaulieu 4008 ZMII, which I love. Because I am a film

scanner at my day job, I can scan my own 16mm for free, but super-8

is actually an added expense. In 2013/2014 I began to process my own

film using the facilities at Negativland in Brooklyn, and while I

mostly lab-process my footage these days, I’ll occasionally

bucket-process, especially for Kodak 7363 Hi-Con B&W stock, as it

is quite simple to do so. My favorite film stock is 16mm Ektachrome,

and I’m rapidly depleting my stock, but I am quite happy to do so.

I used to be precious about my film reserves, but I now realize

there’s no time to wait. Just shoot.

AK: Where did these initial steps lead?

MW: Because

I began to use 16mm on a regular basis, inevitably I was shooting

more than I was capable of processing or scanning, until I was lucky

enough to land a job as a film scanner. Having cut out that expense,

I was able to transfer a decade’s worth of 16mm in 2016, and that

led to the completion of 16+ short films that were in limbo awaiting

finishing funds. I have four feature films – three of which are in

post-production. All of which mainly use 16mm or super 8 film as the

medium, with 35mm, 2.5K, and other video formats mixed in. The first,

I just released, Dailies from Dumpland, will be premiering in Europe

in October, but this summer I’m looking to complete the next

titles, Commodity Trading: Dies Irae & Disneyworld. The fourth

feature, Melencolia, is the one I’ve been working on the longest,

based on a novel I started writing at 15, and it will be released

sometime in 2019 after 12 years of production. My use of 16mm has

evolved to include a lot of in-camera editing, multiple-exposures and

other effects, and I’ve continued my practice of constantly

changing framerates, usually switching between the extremes of single

frame, 12FPS, and 64 FPS. I use a Blackmagic Cinema Camera for any

scenes requiring sync sound, and by sending letters and a prospectus

I was able to use an Arri 535B Sync 35mm camera for the climax of my

film, Melencolia. In addition, I exercised some stock options from my

time as an Apple retail employee to purchase an Arri 35 IIC camera.

(Once I get some funding, I plan to put that camera to good use.)

AK: Did you have any guidance in using this technology or did you work it

all out for yourself?

MW: I

definitely had guidance from some folks as I mentioned above, but

even those who mentored me knew that the only way you learn to shoot

film is to mess up, to learn for yourself, learn your own set of

rules for how to light or work with available light, etc… and so I

feel they guided me to all of the basics, but gave me enough

encouragement to figure out the more important parts on my own. I am

typically a very shy and reluctant person – especially when it

comes to anything that could cost a lot of money – so I needed the

push from these other filmmakers to throw caution to the wind. Now I

shoot with confidence – enough to experiment regularly and push the

limitations of the medium.

AK: What was it that drew you to analogue as a creative tool?

MW: Initially

I was drawn to analog because of the false sense of nostalgia I could

evoke, by the ability to change framerates and shutter angle easily,

by the ability to hand-manipulate, decay, age, and otherwise

intervene with the physical medium. There are a few reasons I think

film still handles better than digital – in terms of creating an

illusion of a physical location/experience. The fact that the grain

is three dimensional, despite being so minute in scale, creates a

depth in the shot image that is otherwise not recreated with a

digital sensor. The organic process, the randomization of the grain

as opposed to the grid of pixels, the ability to animate by hand…

all factors in my decision to continue in analog. That being said,

because of limitations in resources, I am not precious about

finishing in analog. I have a few pieces that do, but it does not

make financial sense for me to create prints, IPs/INs etc… and I am

not lucky enough to have ready access to an optical printer or

contact printer. Instead upon scanning in film, I retain many of the

characteristics I’ve described above, but I’m also able to mix

freely, explore editing the film and digital manipulation in a way

that is under-utilized in the world of “experimental film.” There

are some venues that are particularly dogmatic about film, but for me

it is like oil painting is to acrylic. There are uses for both, and I

like to make messy collages.

AK: What specific models of analogue equipment / stock do you favour, and

why?

MW: Mentioned

above! But I love the Bolex for its lack of battery and its ability

to simulate a mechanomorphic consciousness. I think of my Bolex as an

extension of myself now. I’ve got a beautil Rex-5 I found for $200,

and it’s my 4/5 Bolex. I really wore out my previous ones. My new

favorite stock – other than Ektachrome – is the Kodak 50D &

250 D, but I still do a lot of multiple exposure work on 500T. I’m

using up the last of my Fuji reserves, which is sad, because Fuji

green/red is a beautiful combo. But I am more than content shooting

on those Kodak stocks. Especially the 50D and 250D seem to have so

many stops of latitude that my multiple exposure experiments come out

just as I imagine them.

AK: In what other ways to you experiment with analogue film?

AK: In what other ways to you experiment with analogue film?

MW: One thing I

haven’t spoken on is my hand-manipulation. I use a mixture of

Synchromatic transparent dyes, india inks, scotch tape, acrylics,

liquid acrylics, razor blades, X-acto knives, and bleach. Sometimes

I’ll use other household cleaners to degrade film – Windex and

Ammonia soaked and then washed off and dried. On 16mm and 35mm films

I collage in Super 8 & fragments of 16mm/35mm frames. I’ll use

both motion picture as well as still picture for this practice. The

resultant collage creates several frames with the illusion of motion.

This is seen most prominently in my films Disneyworld, Post-Panoptic

Gazing, and Commodity Trading. Currently I’m working with 120mm

film which I’m scanning in a flatbed scanner – 4-6 frames at a

time – after having directly manipulated the film; I’m collaging

in Aldo Tambellini’s Black TV & Black Plus X – two films he

gifted to me as prints in order to use as collage material for my

upcoming movie Commodity Trading: Dies Irae. I’m using E-6000 glue

to adhere the film. What’s best about that is if you glue super 8

onto 16mm motion picture, it will still project, so long as you’re

careful with the amount of adhesive used. It’s definitely a

difficult and tedious technique, but the results of multiple film

gauges running at once within the frame creates an oscillating effect

between materiality and the illusion that jumps from it. It reminds

me of the shot into the projector gate at the beginning of Bergman’s

Persona. Seeing the material jump to imaginary life and then fall

back into material.

AK: Have you shared any of your skills in the Analogue Arts with others

through workshops, tutorials or other forms of training? How was this

experience?

MW: I

actually wish I could, but whenever I reach out to places in the US

they don’t seem interested in me! Lol. I teach evil digital

moviemaking – Adobe Premiere and Virtual Reality. I’ve never

gotten the opportunity to share my analog stuff!

AK: You also use digital technologies and processes extensively. Could

you talk us through your involvement with these and how you use them?

MW: I

think of the digital as being my new optical printer. I don’t

heavily stack effects or anything like that. I’m not heavy into

compositing, but I still heavily digitally manipulate work. I like to

stick to certain processes – for instance, quick cutting between

multiple lines of action, using blend-modes to pull apart an image

into its positive and negative twin, data moshing and corrupting

files to create keyframe errors (or eliminating the keyframes

altogether), resequencing picture… I often times employ these

methods – almost as if they were employed in a film lab. There’s

a certain automation. For instance, when I data-mosh, I’ll data

mosh an entire movie, then layer that data-moshed movie ontop of its

previous iteration and begin to selectively edit. I take a process

very similar to William S. Burroughs and Francis Bacon. There are

layers and layers of brutal expression. Layers of automation – for

instance datamoshing is an automatic process once you remove the

keyframes or alter the code & similarly layers of

chance/randomness – there’s chance in the destruction of the

elements, there’s a randomness to a certain degree no matter how

well you compose a multiple exposure, or if you bucket-process the

film, the resultant scratches and nicks in the emulsion. Upon

allowing in some chance/randomness/automation, I’ll then edit, to

regain control over the image. And 99% of my work follows this

process. Writing is the same way. Painting is the same way. I never

come out with something that’s just perfect for me. I need to beat

the shit out of my work.

AK: The Digital Revolution has opened up the World of High Quality, Low

Cost filmmaking and photography for a lot of people. It's still

relatively expensive to use analogue movie or stills stock and it's

also generally a more time-consuming and complicated way of working.

So, what's the attraction? What is it that makes the expense and

effort worthwhile in the 21st Century?

MW: Actually,

I disagree. If you factor in the cost of hard drives, and shooting on

a Black Magic Cinema Camera – for digital right now, at least in my

opinion, there’s really one viable option. Shooting RAW. And RAW is

huge!! So even in the digital space there’s a lot of expense. I go

through hard drives in no time. With film, I’m more economical. The

restriction of the roll forces me to think about what I want to

shoot, and the juxtapositions on the roll serve as my in-camera

edits. I don’t have as much room for error and it’s like my brain

kicks in. If you’re driving in a video game, you tend to make more

mistakes than when you know your life is on the line. Now I cannot

understate the privilege I have of access to a film scanner. The film

scanner has changed my entire work. It is the sole reason many people

know who I am now, or know any of my work. I had no way to scan

thousands of feet of 16mm. So, mind you, I’m coming from the

perspective of a person who can get film scanned for free. But beyond

that, I really do think good quality digital is ridiculously

expensive. (I use my iphone, of course, but with the intention of

compromising the quality or using it for still-image stop motion and

the like. Truth is, I still feel I have more control over the image I

create in analog than in the RAW digital capture.)

AK: What kind of future do you see for analogue creativity in a digital world? We can see analogue-digital hybrid art becoming an interesting new form that filmmakers and artists can experiment with. Is this something you like to do with your own work?

AK: What kind of future do you see for analogue creativity in a digital world? We can see analogue-digital hybrid art becoming an interesting new form that filmmakers and artists can experiment with. Is this something you like to do with your own work?

MW: For

this I have to shout out to my good friend, Karissa Hahn. Karissa

shoots analog films with digital subjects and finishes analog

typically. I shoot analog and digital hybrids trying to arrive at an

organic reality, and often depicting mechanomorphic and digital

degradation, which is then matched by my process of

automation/randomness/corruption/brutal re-ordering. I think we have

complimentary processes in that way. I think the truth is we live in

a hybrid world. Digital will always have to negotiate the

analog/organic, and the analog/organic is too tedious for humans to

replicate as material, so digital has its benefits in simplifying and

codifying the infinitude of our being. Both are fatally flawed –

and in that way both represent characteristics of human

consciousness. Both methods degrade no matter what. The analog is

needed, however, as a foil for the ever-digital world. The objecthood

of an analog piece is a statement – although sometimes a nostalgic

one – against the infinite serialization of the digital “object”.

I think these are like oil and acrylic, though their DNA is slightly

more complicated; but I use them for their strengths, I exploit their

weaknesses, and then I try to manipulate my audience based on their

aesthetic/emotional attachments to various media. We all have an

individualized understanding of what it is to be experiencing super 8

or 16mm or 35mm, though many folks cannot verbalize it – and many

cannot even perceive the difference. But I do believe there is an

unconscious connection we have to these varieties of motion picture,

and, for those of us who shoot, we begin to see the nuances of

cameras, lenses, stock choice, etc… In the end, I want as many

tools at my disposal as possible. If I’m dirt broke and all I have

is an iphone I’ll use that, but, for instance, if I want to create

an all-encompassing illusion, with a density to it, with the

perception of “being there” in the film, I’m going to go for

35mm or 16mm. If I wanna shoot all day without worrying too much

about cost, digital is the happy medium. And it’s so much easier to

record sync sound to. Super-8 gives me a tool for playing with

nostalgia, placing an illusion out of a contemporary context; the

ability to wear it down. But, in conclusion, the medium itself is of

no matter. It’s the main thrust of the piece that chooses the

medium for me, and all of those aesthetic considerations are taken

into account based on a wholistic approach to the work and the

thematic/philosophical underpinnings that have brought it forth in my

consciousness. Beyond that, the medium coordinates with the meaning,

and it is through that symbiosis that I create. I never make

aesthetic considerations above thematical/theoretical decisions. They

should happen in tandem. For better or for worse, a tree or flower

does not grow the way it does for its own aesthetic admiration. It

grows as part of its function; in the same way I view art as a

process reflective of the innate function; without the function,

there’s no point to discussing the medium or the aesthetic tools

used.

AK: Thank you very much, Michael, for taking the time to answer our questions.